Donald Trump is waging a trade war with China (and everyone else, but especially China), premised in part on the notion that China has stolen loads of US jobs. Many politicians and commentators alike are firmly set against Trump’s tariffs, but concede the notion that China has displaced the US from manufacturing.

This argument generally goes that some form of fair (cheap labour as rural Chinese workers were pulled into the workforce) or unfair (massive state subsidies, an undervalued currency, and generation of “overcapacity”/failure to boost domestic consumption) have driven American jobs overseas. China’s (to some, unfair) entry to the WTO in 2001 went to massively boost this adverse trend.

However, the data don’t exactly back this up.

On the surface, we might make quite a simple observation. The US unemployment rate is very low and the economy is likely close to full employment. This implies that there are not loads of Americans who want to do those jobs that tariffs are trying to onshore.

However, the headline unemployment rate being low doesn’t quite address the core of the issue here. The big issue for some is that manly jobs in factories and the like have been shrinking in both absolute terms and as a fraction of total jobs for decades now. These manly jobs are quite important for the manly men who want to do them. Instead, these manly men are getting shoe horned into (girly?) services jobs, which must suck.

For real though, this transition is probably quite an important cultural shift for America. Manufacturing jobs offered non-college educated men a respectable career, where they could earn a good salary and feel proud (and manly). That isn’t to say that massive shifts in workplace norms over recent decades which have massively improved outcomes for women and non-white workers are not a good thing. However, the blight of (mostly white) men is an important theme and likely goes some way to explaining the success of politicians like Donald Trump.

So it looks like there is quite a significant bunch of men who used to do pretty well respected jobs who are now pretty dissatisfied, that isn’t captured by that unemployment print. This is important. The question of just what happened to those jobs is equally important.

If these jobs migrated overseas, then we should see that manufacturing activity in the US has fallen quite sharply.

However, we don’t see this in the data. What we see is manufacturing output has largely moved sideways since 2010, and manufacturing output is over 3x the levels of say the 1970s, when manufacturing was a much larger share of US employment.

We have US manufacturing output being much higher at present than in the 1970s, while employment is much lower, i.e. output per employee has risen quite sharply. This suggests that the big losses in manufacturing employment is actually a product of the industry’s success – gains in productivity and capital deepening have meant that firms needed less employees to do the same work.

Consistent with the view that manufacturing job losses are more so down to the sector’s productivity gains than any migration of jobs to China, manufacturing output entered a major stagnation since 2010s, which the NY Fed largely puts down to stagnant productivity growth. While productivity largely stagnated, manufacturing employment actually ticked up, growing from 11.4mn in January 2010 to 12.7mn in May 2025. The Chinese economy continued to expand at very high rates through that period, but there were no net manufacturing job losses in the US.

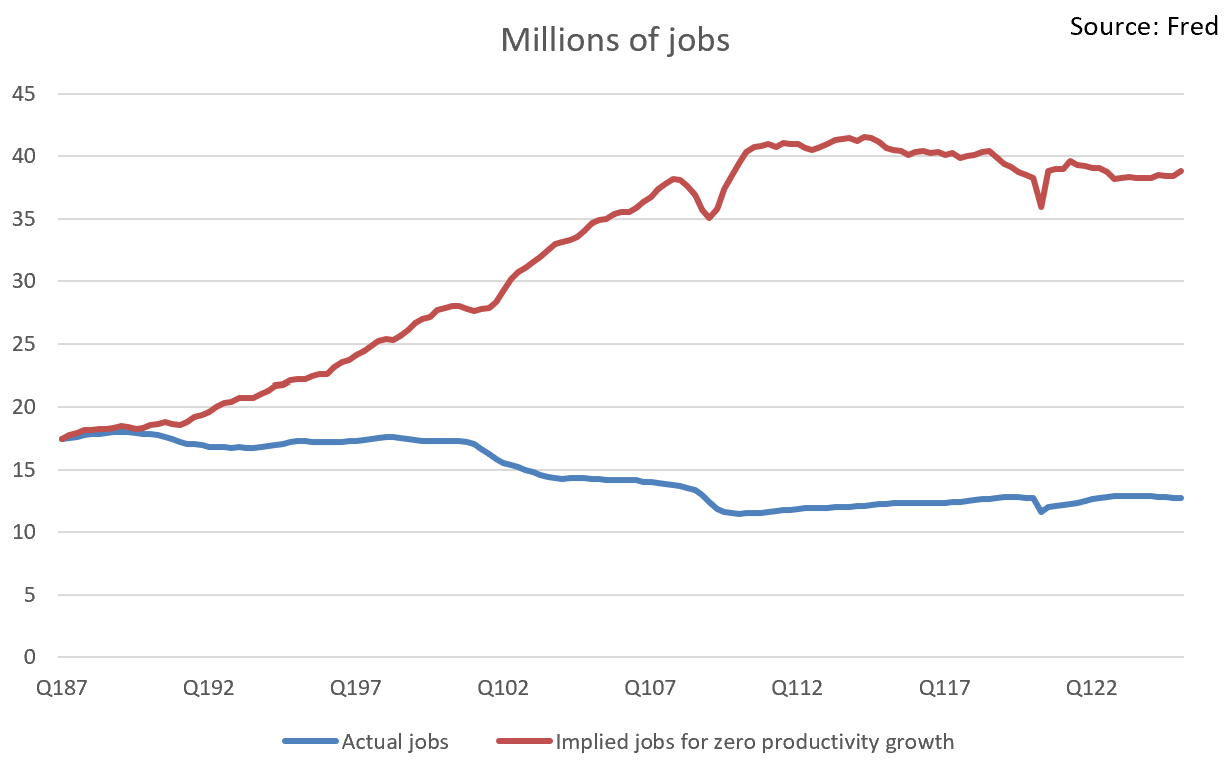

We can actually illustrate our broader point quite simply. Obviously, there have been productivity gains over recent decades, so output per worker has picked up. However, we can compare actual output per worker with a hypothetical scenario of zero output per worker (productivity) growth, finding the ratio between the two (right axis below).

We can then take that ratio and multiply it by the number of jobs in Q187 (our first year of full data coverage). This will then give us an estimate of the number of manufacturing jobs required for the same level of manufacturing output should the US have had 0 growth in manufacturing productivity. There you go, I found 2.6mn extra jobs.

I’m not trying to claim here that there were no job losses in the US due to China’s success in manufacturing. However, it appears that most of the woes for the US manufacturing workforce were a product of productivity gains, and not due to China.

JB Macro is my blog, where I splurge out my brain. I’m building a following for my passion, writing about economics and markets, and it would be really great to have you on board. Please consider pressing the subscribe button below (it’s free!!). Thank you, James.

This newsletter is for informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or an offer to invest. The views expressed herein are the opinions of JB Macro exclusively. Readers should conduct their own research and consult with professional advisors before making any investment decisions.

Automation explains most of the change. Productivity Growth is more accurate, but too Economics-Speak to work in the real world. Krugman had a detailed and definitive post agreeing with you about a month ago. It’s worth reading. If what you say is true, and I’ve no doubt, what is the meaning of blowing up the supply chain via tariffs?