Interest Rates Don’t Matter?

Corporate Profits Drive Investment, Not Financing Costs

I thought for this note I could write a really nicely structured piece on the intersection of UK politics, fiscal policy, and growth.

Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham appears to be in the process of either successfully or unsuccessfully launching a leadership challenge against PM Keir Starmer, who is doing quite badly in the polls.

Burnham attracted some attention with a soft leadership launch in September, in which he said “We’ve got to get beyond this thing of being in hock to the bond markets,” a sentiment which he maintains, but has also insisted has been “deliberately misinterpreted.”

I don’t think Burnham intended to advocate for massively looser fiscal policy (although he should learn that the words he uses do matter). Nevertheless, markets have decided that his premiership would mean increased deficit spending relative to the current government, with gilt markets reacting accordingly (higher yields).

The piece I wanted to write would 1) quantify the shift in long-end bond yields from a variety of fiscal shocks, to provide an estimate of the likely yield shift as expectations of modestly looser fiscal policy under a potential Burnham-led government set in; 2) estimate what this would mean for fixed investment and GDP growth.

Given the second task is the more arduous of the two, we started with that. And of course, stumbled into the typical issue with economics – the theory is largely not backed up empirically.

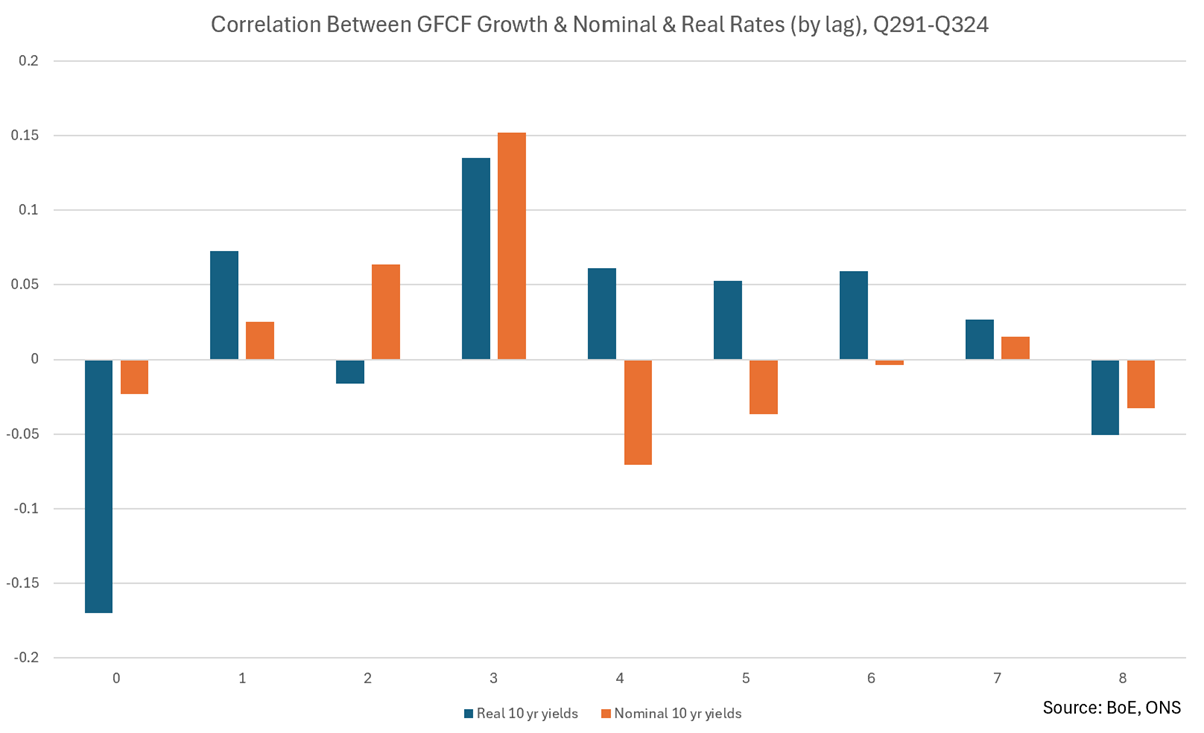

When we began to try to model fixed investment on both real and nominal long-end rates, we found very little relationship. From the theory, we would expect nominal and real rates to be negatively correlated with fixed investment, as cost of borrowing drives decisions related to credit financed investment (higher rates = less investment).

We do find lag 0 real 10 year yields have a very modestly negative correlation with fixed investment, but this is way too low to be useful in modelling investment. Regressing investment q-o-q growth on real rates gives an R^2 of just 1.7%, suggesting real rates explain almost none of the variability in investment growth. Indeed, real rates have a p-value of 0.168, meaning they are not statistically significant as an explanatory variable.

This finding (which is not fixed by controlling for the Brexit and Covid periods with dummy variables nor fixed by focussing on earlier periods of the sample), scuppers the original plan we had. However, it does lead itself to a new set of questions. Namely, what drives UK investment?

The theory tells us that beyond real rates, corporate profitability is a major driver of investment. In fact, considering profitability as more important than real rates is somewhat conventional – Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s stock response when asked about the potential for rate cuts to further stimulate an AI boom has been to talk down the impact of a few 25bps cuts on AI investment. The idea here is that AI firms are fixated on potentially eye watering levels of profitability – modest shifts in real rates simply do not matter in this context. Current profitability is a much better measure encapsulating financial firepower and confidence.

Running the numbers, profitability is a statistically significant (p value = 0.003) driver of UK investment growth over Q297-Q325, providing some support of a rates don’t matter, corporate profitability does theory.

This period has been tumultuous for the UK to say the least, containing many, many major impediments to fixed investment (GFC, Brexit, Covid). That said, it might be premature to cast aside real rates just based on this experience. We can of course look overseas (separate work I have done for the US suggests that real rates are a statistically significant driver of investment, but not nearly as important as corporate profitability). However, we want to retain our UK focus here, so we can look further back in time.

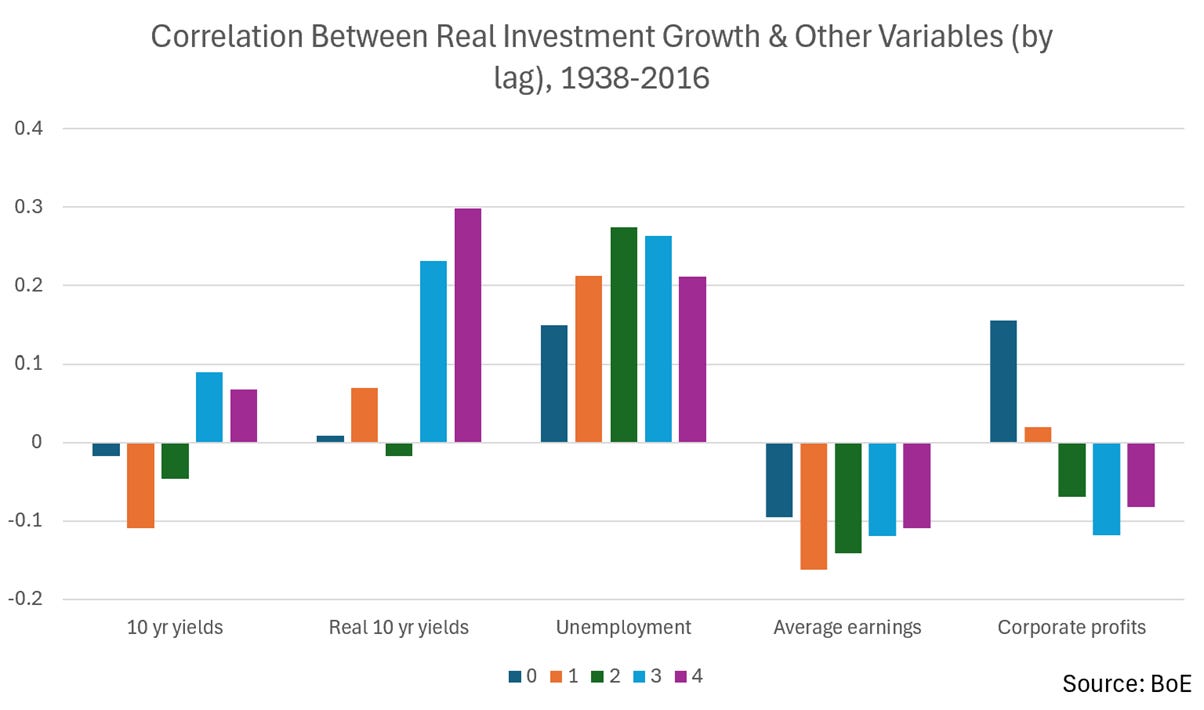

This means using the BoE’s millennium of macroeconomic data, a truly excellent data source. Considering data between 1938 and 2016, there is pretty much no correlation between real yields and real investment growth (see chart below). Nominal yields have a very modest negative correlation to real investment growth at lag 1. Corporate profits have a stronger (positive) relationship. The more consistent relationships come in unemployment and earnings, which feature greater correlations and a preferable semi-bell shaped pattern in annual correlations which gradually rises to a peak and then falls off. However, causality may be a problem here. The data might be skewed by heavy investment (industrialisation periods) which coincided with rising unemployment.

Taking the data at face value, it suggests that real and nominal yields are the least important of our five variables in explaining investment growth.

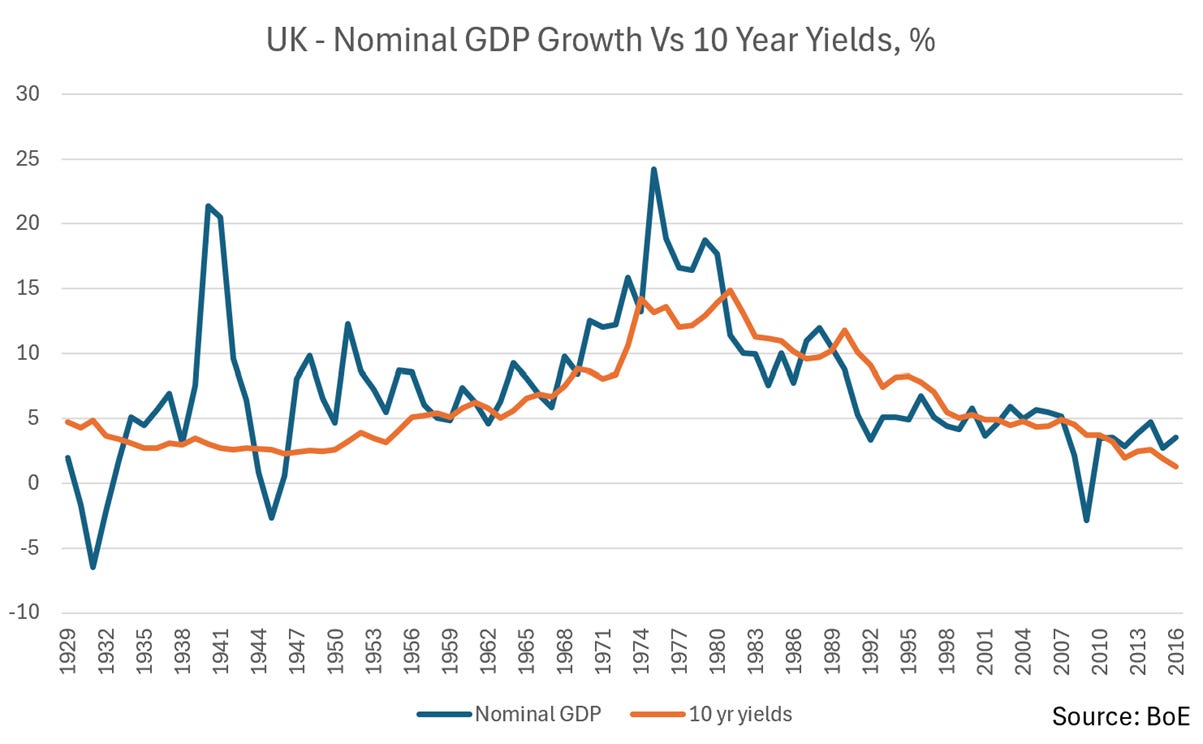

While this feels weird on the surface, we could easily flip the consensus narrative (financing costs matter) on its head and still find that interest rates are important. Long-end rates are a proxy of investment returns in an economy, which is why they often track nominal GDP growth (see chart below). In periods of high profitability, and high investment, the cost of capital or desired returns will likely be higher. This means we can often find that high interest rates coincide with high growth, rather than high interest rates coinciding with low growth (and low rates with high growth). This puts interest rates as an endogenous product of growth as opposed to an exogenous driver of growth.

So there we have it, interest rates may not be the be all and the end all. Although they do probably matter. Quite a lot. Sorry for the clickbait title.

JB Macro is my blog, where I splurge out my brain. I’m building a following for my passion, writing about economics and markets, and it would be really great to have you on board. Please consider pressing the subscribe button below (it’s free!!). Thank you, James.

This newsletter is for informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or an offer to invest. The views expressed herein are the opinions of JB Macro exclusively. Readers should conduct their own research and consult with professional advisors before making any investment decisions.