Consensus now has it that US tariffs are inflationary for the US, in the near term.

Last year, consensus had it that tariffs were inflationary for the US, full stop. Into November’s election, the bet was that modest tariffs striking into a tight US labour market and more broadly a very strong US economy would trigger inflation which would drive some second round effects, disrupting the Fed’s battle against inflation. Yields and the dollar would rise.

However, this assumption changed through the first months of Trump’s presidency. The consensus now has it that the combination of the tariffs being much, much larger than expected and a weaker economic outlook means that tariffs will be inflationary in the near term, but might be disinflationary in the medium term.

The understanding is that the initial supply shock will drive up prices for tariffed goods, while firms might also increase the prices for non-tariffed goods and services in order to either offset increased costs on tariffed goods or due to profit seeking. After that, the weakened demand backdrop would dominate (given the supply shock was a one-time shock, i.e. was not persistent).

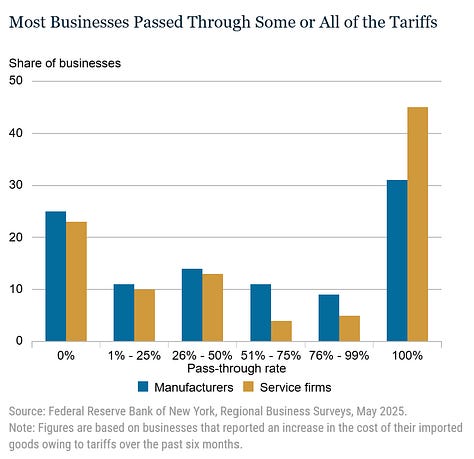

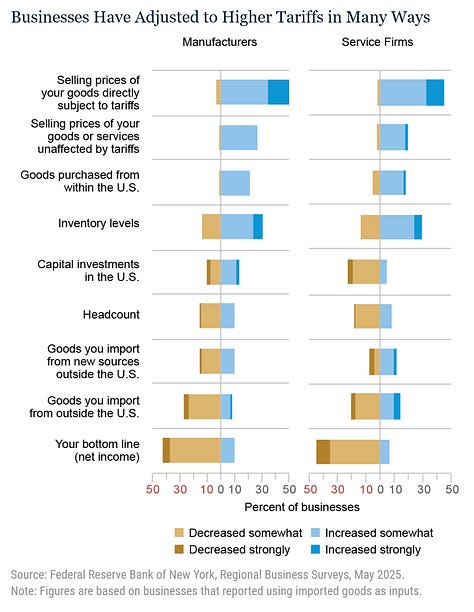

As to tariffs driving a near term jump in inflation, we find evidence for this in this survey data from the NY Fed. To caution, the field dates were 2-9 May, which was when tariffs on China were at 145%, but the main takeaways likely still stand. For me, these are:

A decent chunk of firms (30%+) are passing on 100% of tariff costs.

An alarming number of firms are increasing prices within a week of tariff increases (36% for manufacturing, 29% for services). This means that selling costs were likely jacked up in response to the higher initial "reciprocal" rates and the higher China tariffs. (The key question is, did prices fall instantly as tariffs fell too?)

Many firms reported increasing selling prices of goods not impacted by tariffs.

Tariffs have largely not led to firms increasing capital investment in the US, with services firms reporting tariffs have led them to lessen capital investment in the US.

Tariffs are a huge headwind for profits across both manufacturing and services.

Tariffs driving higher inflation makes sense. Around 10% of the consumer basket is imported, and this 10% would now be tariffed at an effective rate of 15-20%. That implies a 1.5-2.0% increase in the price level if increased costs are passed along (and margins maintained), just via the impact of higher prices on imported final products.

The impact on inflation from tariffs on non-final goods is likely to have a much more profound impact on prices, for instance, with this note from the San Fran Fed indicating a hypothetical 25% effective tariff rate applied to both final and intermediate goods could increase the price of investment goods by 9.6%. Higher prices for equipment would cascade to higher prices for domestically produced goods.

However, we haven’t seen this at all in May’s CPI report.

CPI-U rose just 0.1pp to 2.4% in May. Per the chart below (from the BLS), month on month inflation looks mild compared to recent reads.

Inflation on items that you’d expect to be more hit by tariffs also looks quite fine. Apparel prices fell 0.9% m-o-m, following a fall of 1.0% m-o-m in April. New vehicle prices rose 0.4% m-o-m, following zero increases in April.

Further, per NY Fed survey data, consumer inflation expectations one year ahead fell from 3.6% y-o-y in April to 3.2% in May.

This raises the question of where is the inflation?

There are a few possible answers:

The data we have so far is incorrect, and will be revised. CPI data tend to be quite good, so this appears unlikely.

The inflation is delayed, and will, hit in the coming months. However, this contrasts with NY Fed survey data that firms are passing on tariff related cost increases very quickly. Perhaps firms are drawing down inventories of lower priced goods first, before increasing prices? This looks unlikely.

There will not be an increase in inflation because tariffs have not increased costs by much, which might reconcile with surprisingly low tariff receipts in April (well below levels consistent with effective tariff estimates of 15-20%). Further supporting this, imports are less than 15% of the US economy. However, it is quite hard to believe that a jump in tariffs only comparable to the 1800s would have such little impact.

There will not be a significant increase in inflation because the demand destructive nature of tariffs is dominating.

For me, outcome 4 appears to have become more likely, and it implies quite a downbeat outlook for the US economy (which recent revisions to labour market data also support). This suggests that the Fed may end up behind the curve, driving a much more aggressive easing from the Fed, putting into question end-2025 SOFR pricing of 3.9% and end-2026 pricing of 3.4%. (It’s probably worth noting too given escalations in the Middle East, that a surge in oil prices would be less inflationary hitting into a weak demand backdrop)

So there we have it. An aggregate supply shock hitting into weakening aggregate demand might just lower output and not increase prices.

JB Macro is my blog, where I splurge out my brain. I’m building a following for my passion, writing about economics and markets, and it would be really great to have you on board. Please consider pressing the subscribe button below (it’s free!!). Thank you, James.

This newsletter is for informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or an offer to invest. The views expressed herein are the opinions of JB Macro exclusively. Readers should conduct their own research and consult with professional advisors before making any investment decisions.